Millions of consumers have turned away from PayPal’s popular voucher-sharing service, Honey, after it was alleged to have exploited users and deceived advertisers.

It was claimed that the app worked by replacing "referral links" used by influencers to monetise digital content like podcasts, newsletters and YouTube videos with its own links, taking their place as the source of any purchase made in an online shop, enabling PayPal to claim any commission offered by the retailer.

At its peak, the service had more than 20 million active users of its Google Chrome browser extension. But as of January 2026, it had lost nearly half of those users and had been suspended from the Chrome Web Store.

Google has removed the Honey extension from its Chrome Web Store

Google has removed the Honey extension from its Chrome Web Store

So how did the voucher-sharing service bought by PayPal for $4 billion in 2020 fall from grace?

If you shop online or use social media, you’ll likely be familiar with Honey and how it claims to work: install its app or browser extension, shop as you usually would, and “it does all the work” finding you available voucher codes to reduce the price you pay at checkout.

For years, Honey continued to grow in popularity with few questions asked about how it knew about these codes. But online retailers began to cry foul after noticing the vouchers being shared with Honey users weren’t just general promotions, but also secret codes intended for friends and family, or select groups like emergency service workers.

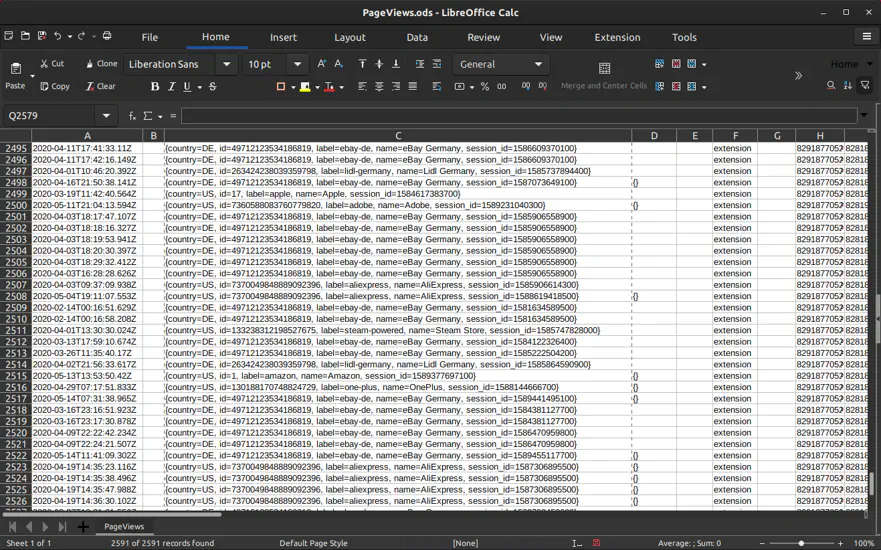

An investigation by DataRequests.org revealed that, once installed, user-entered codes are immediately transmitted to Honey’s servers, even if the user doesn’t opt in to share it when prompted.

We can’t be sure what Honey does once it has these codes, but YouTuber and journalist MegaLag reported that retailers who have contacted the service and requested their removal are referred to its “partnerships team” and encouraged to sign up with them to allow greater control over which voucher codes are shared with Honey users. Businesses that decline to join the scheme were reportedly told to stop using multi-use voucher codes if they didn’t want the coupon app to scrape them and share them with its users.

While, on the face of it, voucher-sharing services may appear to be a win for savvy shoppers, retailers who haven’t partnered with these sites and whose coupons were scraped from legitimate customers have resorted to raising prices across the board to compensate for lost revenue.

But why do retailers offer voucher codes if they don’t want people to use them? Each coupon will have a specific purpose: 10% off for signing up to their newsletter and providing your email address for marketing communications, and 25% off as a reward for loyal, returning customers.

Retailers will have done the maths on whether the deals they are offering are viable for the number of people they expect to take them up. When those codes go from an audience in the hundreds to hundreds of thousands through voucher-sharing apps, they may be less inclined to run similar promotions in the future if it isn’t viable for their business.

Sharing voucher codes has been possible since the earliest days of internet shopping, but, in its infancy, sites relied on users to exercise their judgment about which codes to share. Now automated apps and extensions “do all the work”, and, certainly in some cases, appear to harvest vouchers entered as users shop without their knowledge or consent. It’s apparent that, for some of these services, its users are the product – with browsing habits and shopping data shared with its selected partners and businesses which don’t sign up missing out on the benefits they originally hoped their promotions would deliver.

It’s worth reflecting on the $4 billion price that PayPal reportedly paid to acquire Honey in 2020. Why did one of the world's largest financial technology companies want to spend so much for a browser extension that saves people money? It's millions of users, and their data was likely a factor in the purchase.

DataRequests.org revealed that the Honey browser extension records websites visited - tracking not only products purchased, but also items looked at but decided against purchasing, as well as how long sites were viewed.

While some of the dubious practices exposed may be exclusive to Honey, voucher-sharing services are thriving. Even Microsoft’s Edge browser now includes a similar service built into some versions of the app, resulting in the tech giant, like PayPal, being on the receiving end of class action lawsuits over the way these services operate and the lack of transparency provided to users.

Voucher-sharing apps are a fantastic concept when used responsibly. However, it seems some less-than-ethical practices have set in, such as harvesting voucher codes without the user's permission, snooping on your shopping habits and sharing information with the app's commercial "partners", as well as potentially exploiting small businesses whose vouchers were unknowingly being shared.

It might seem counterintuitive for the Jersey Consumer Council to advise against using shopping tools which promise to find you the best deals, but as well as trying to save money, one of our core principles is to raise awareness of dubious practices affecting consumers and provide information that can let you make informed decisions about how you shop.

As we’ve said countless times before: if a deal seems too good to be true, there's probably a catch somewhere.

Jersey Post increase collections from Amazon depots to resolve recent issues

Jersey Post increase collections from Amazon depots to resolve recent issues

January planning: Think ahead and save

January planning: Think ahead and save

Make your consumer rights your New Year’s resolution

Make your consumer rights your New Year’s resolution